Building a Better Pencil

Rosh Hashanah Sermon, 5773

By Rabbi Rafi Rank

Midway Jewish Center, Syosset, NY

|

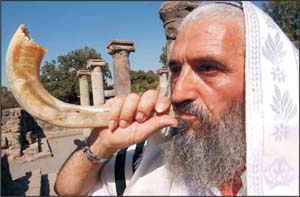

Shofar blowing at an ancient synagogue in Israel. |

Shanah Tovah, everyone. So good to see the Midway family gathered together for the New Year. Let us, during these Aseret Yemei Teshuvah, these Ten Days of Repentance, create those good prayers that will move us and the energy around us to health and fulfillment, to wisdom and peace, to all the good stuff that makes us feel alive in and focused on the days ahead. And may the blessings we are soon to enjoy impact on the people we love so that together we may go forward with the power and strength that allows us to enter a New Year with confidence and purpose.

There was once an investigative reporter traveling across America in search of interesting stories for a newspaper she wrote for. She came across a town in mid-America that, at first blush, seemed like every other town she had visited, but there was something odd about it, something very retro that she could not quite put her finger on. It all became clear to her as she strolled down Main Street that this was a town where no one had in hand a cell phone, an ipad, or a laptop, but everyone in town jotted notes down on a pad of paper with not even a pen, but a pencil. A pencil! She couldn�t remember when she had seen so many people with pencils in hand. So she stopped a clerk in the store and asked, �Excuse me, but can you tell me why in this town everyone uses a pencil?� And the clerk responded, �You must be from out of town, because here we all use pencils. These are special pencils: Goldberg's pencils. These pencils are the wisest pencils in the world. When you write with these pencils, they actually make you feel better.� �What makes these pencils so special?� asked our travelling reporter. �No one really knows,� answered the clerk. �The pencils are produced in Goldberg's factory. No one is permitted to enter the factory, but that Mr. Goldberg, he really knows how to make pencils.�

The reporter knew a hot story when she came across one so she had to in some way infiltrate the Goldberg Pencil Factory. She finds out the address, parks her car several blocks away and then in the dead of night, breaks into the factory through a back window and waits for the morning to witness the production of the famous Goldberg pencil. Sure enough, 8:00 AM, the door to the factory opens, and in walks Mr. Goldberg, a gentleman in his seventies, who has done nothing in life but produce pencils. The reporter watches him put on an apron, gloves, goggles and proceed with the production of pencils in silence. Nothing is out of the ordinary as far as pencil production goes but just before 5:00 PM, when Mr. Goldberg has finished 100 beautiful, yellowish orange no.2 pencils, he places them all upon his work table and addresses them as follows:

Kinderlach--My dear little pencils. You are about to go forth into the world'schools, businesses, homes, and so forth. Remember the following important lessons: One. Everything you do will always leave a mark. Two. If you�re not so happy with the mark, don�t worry, you can erase it. Erase it quickly because the longer you leave the mark the harder it will be to erase it. Three. You will undergo some very painful sharpenings, but you know what�it will make you a better pencil. Four. At some time, you may end up in a desk for years or behind a shelf or lost on the road, abandoned, forgotten, alone. At those times remember�what makes you a pencil is not what's outside of you, it's what's inside of you. And finally kinderlach, my dear pencils, in order to be the very best pencil in the world, you have to be held and guided by the hand that holds you, so respect that hand, for it will help you become what you were put on this earth to be: a pencil. And with that address to the pencils, Mr. Goldberg turned the lights out, went home after a day's work, and the reporter knew what made the Goldberg pencil the most special pencil in the world. (After an Internet story by Louis Finkelstein).

There was a time in the history of humankind when great philosophers would discuss and debate exactly what the good life was, what people should do to maximize whatever pleasure or contentment they could derive from their tenure on earth and the answers typically involved something more interesting than eat, drink and be merry. Carlos Fraenkel, a philosophy professor at McGill University in Montreal, has, as of late, written about a very curious philosophy class that he has conducted surreptitiously for a group of eager students (Jewish Ideas Daily, September 4, 2012'spinoza in Shtreimels). If the idea of conducting a philosophy class in secret, at the beginning of the 21st century, strikes you as bizarre, consider the students he was addressing: a small group of Satmar and Lubavitch Hasidim whose faith has been shaken. Are the miraculous stories of the Bible true? Are the mitzvot their community follows so rigidly really representative of the will of God? Is the sheltered life they live, now so easily compromised by the information and graphics that are downloaded onto one's computer, really an honest way to live? So many questions! One of the hasidim present explains that what their little group is doing would be regarded by their respective communities as worse than an extramarital affair. Infidelity, after all, is merely yielding to temptation of the flesh, but study Plato or Socrates or Aristotle�that might end in the loss of one's Jewish soul. These classes, you understand, must be held secretly and so the initial meeting unfolded in a place you wouldn�t typically find Hasidim: in a bar.

Can you imagine growing up in a world where a certain group of authorities regulate what passes for truth, where personal questions about faith are forbidden, where personal questions about the community's cultural structure are off limits, where objections raised must be done with the greatest of delicacy lest you upset the traditional norms which themselves may be the very subject of your discontent? It sounds horrible, yes? It sounds horrible to me. And I suppose we can thank God that we have chosen to live a life in which that type or rigidity or authoritarianism is not tolerated. But before we raise the flag of triumph in celebration of our freedom, in the spirit of pursuing an examined life, let's ask ourselves a few questions about life outside the strictures of a closed-Hasidic world.

Many of us will remember that in May of 1979, a little boy by the name of Etan Patz disappeared in New York City. In spite of an intensive search for the boy or in the very least his remains, he or his remains were never found and in 2001, he was declared dead. This past year, over thirty years since his disappearance, a man came forward and confessed to the crime. Some have criticized the NYPD for being too quick to accept the confession�he's a man with a history of mental illness so there is legitimacy to that criticism�but what is striking about this case is not so much the man's confession as that in the early 1980's, according to the man's sister, the man had said something that indicated he was involved in if not guilty of little Etan's murder. It was, in essence, and here we can quote the words of the sister as reprinted in the New York Times, �an open family secret that he had confessed in church� (NYT, May 26, 2012).

Wait! An �open family secret�? A six year old child is missing and possibly dead. His heart-broken parents have been searching in vain for their child or his body for years. You know that your brother, your nephew, your son, your friend�whomever!�may possibly, not certainly, but possibly, be involved in this tragedy�and you don�t say anything? You don�t raise a question? Whose holding your tongue? Whose keeping you from going to the police? What code of ethics are you following that would suppress any attempt on your part to, in the very least, examine the veracity of the confession? What social structure are you caught in that keeps you from speaking out?

This past June, Jerry Sandusky, the long time assistant coach of the Penn State football team, was found guilty of 45 of 48 counts of sexual abuse with young children. Louis Freeh, the former director of the FBI, was commissioned by the Penn State Board of Directors to investigate the school's handling of reports about Sandusky's misconduct. The report noted that Sandusky's suspected abuse of children was known to officials at the school as early as 1998. And following that, various reports came to school officials about Sandusky's young visitors on campus. Papa Joe Paterno, the iconic head coach of the Penn State football team knew, the athletic director of the university knew, the senior vice president of finance and business knew, people in positions of power knew something was very wrong and no one took the steps necessary to stop it. Why?

Freeh looked into this question. According to the report, the silence and inaction mostly had to do with the fear of the consequences of bad publicity. I may be wrong but I read that to mean that publicity of that nature could have resulted in the university's loss of big bucks. Money. The report cited other factors as well. It cited an egregious lack of sympathy for the child victims of sexual abuse, a university culture that had an unhealthy obsession with football, but the factor that strikes me as most damning was a university president who discouraged discussion and dissent. What in God's name is a university about if not discussion and dissent? So here you have a culture, a university culture no less, where the unspoken rule is don�t question, don�t disagree, don�t upset the system, don�t challenge the status quo, and don�t upset the apple cart.

The stories of Eitan Patz and Penn State may be extreme examples, or are they? I wonder how often we find ourselves in predicaments, in our families, in our businesses, in our social circles, where some wrongdoing is covered up because the pressure to keep silent is very real, or the fear of being the whistle blower is too much to bear, or the courage to be the bad guy, the one who is going to not conform, is simply absent. The message seems to me very clear. You don�t have to be a Hasid to end up caught in a cultural or social structure that demands your submission or your silence.

Back to the bar. Back to Dr. Fraenkel's philosophy class with the Hasidim. So one of the Hasidim in the class made a very telling observation about his life. He suggested that Socrates, the great 4th century Greek philosopher who believed in reflecting on one's life, might have in some way found a great advantage to being born into a Hasidic community. And that is because when you are a Hasid, you are so out of synch with the rest of the world, because your calendar is strange and your dress is strange and your accent is strange, everyone looks at you as weird because you�re so weird, you can�t help but stand out. You can�t help but examine the point of doing whatever it is your community has told you to do. That is to say, you have to question your life, and the manner of your living, constantly. I don�t really know how often Hasidim actually question what they are doing�for many, I would imagine, it is the absence of questions which is the very appeal of that type of world�but for this Hasid, he found himself questioning his life all the time. You know�that's not such a bad place to be. How can one possibly examine one's life without delving into a host of questions about what it means to be human, to be alive, to live fully, to be me? You know, those are Jewish questions. I know�you don�t have to be Jewish to ask those questions, but our community values and respects self-analysis, introspection, questions that would move us to examine how we live.

The tale of Bernstein and the rabbi. Bernstein and the rabbi were not exactly the best of pals. Bernstein was a tailor from the old country and even though he never practiced as a rabbi, he really knew more Torah and was not above correcting the rabbi from time to time. The rabbi was a little jealous of Bernstein's learning, and he was particularly jealous of his bimah and whom he permitted to ascend it. The rabbi would have preferred to keep Bernstein off of it, but he knew that Bernstein was the most learned in Torah of the entire congregation and moreover, when it came to Rosh Hashanah, Bernstein was the best ba�al teki�ah, the best shofar blower in town. So the two of them had a working relationship. Bernstein didn�t criticize the rabbi too much and the rabbi let Bernstein onto the bimah for important functions�being gabbai, reading Torah, and blowing shofar. But this year was different. Bernstein comes to the rabbi and says, I�m not blowing shofar this year. The rabbis says, Bernstein, of course, your blowing shofar this year. You�re the best ba�al tekiah in town and I have no one else. Bernstein replies. No. I�m too old and I�m too tired. Enough already. It's time for new blood on the bimah and I have someone who will blow shofar for you beautifully. A new member. She's terrific. She�ll be our ba�alat tekiah this year. The rabbi was not happy, but what was there to do? Bernstein was refusing to blow shofar. Rosh Hashanah arrives, Shaharit begins, and soon the cantor reaches the service for the blowing of the Shofar. A woman holding a beautiful long Yemenite shofar ascends the bimah along with a teenager. The rabbi whispers to Bernstein, She, with the shofar, I understand, but whose the kid? Bernstein says, Don�t worry, it's her son. The rabbi says, what's he doing on my bimah? He's coming up to hear his mother blow the shofar. The rabbi says If he wants to hear the shofar, let him stand in the congregation with the rest of the people. I�m going to tell him to return to his seat. Bernstein says, Don�t do that and calm down. He needs to be on the bimah to hear the shofar blown. He's deaf. The rabbi replies, Bernstein, you drive me crazy. If he's deaf, then he's exempt from hearing the shofar. Bernstein says, I know he's exempt but he doesn�t think he's exempt. He wants to hear the shofar blown so when his mother sounds the shofar, he places his hand on the shofar and senses the vibration of the instrument. That for him is hearing the shofar. The rabbi replies, Bernstein, putting your hand on a shofar is not hearing a shofar, it's feeling a shofar. And with that Bernstein replies, I know. When the shofar is blown, he feels the shofar. He's probably the only one in the congregation who actually hears the shofar the way it was meant to be heard�by feeling it move your soul.

Within the Halakhic literature, there is a question raised about a choice a Jew has to make on Rosh Hashanah. The problem stems from a man who lived in a town with two shuls. Wherever there is a town with Jews, there is always a minimum of two shuls. On Rosh Hashanah, the man did not know which shul to go to. In Shul A, the cantor sang like an angel, stirring your soul to the very core. The rabbi spoke pearls of wisdom. And the shofar blower couldn�t get a single tekiah out of his instrument. With the greatest of difficulty and painstakingly, the ba�al tekiah would torture the congregation with a terrible sound. In shul B, the cantor was not so aye-aye, and the rabbi was a walking sleeping pill. But the Ba�al tekiah was like the first chair in the New York Philharmonic. A shofar sounding so stirring like nothing he had ever heard in his life before. Which shul should he go to'shul A with the inspiring service but the lousy shofar blasts. Or Shul B, with the uninspired service but the terrific Shofar blasts? Let's vote� According to the Halakhah, Shul B wins because great davening and a good sermon�you can hopefully access that on many Shabbatot during the year. But on Rosh Hashanah, the special mitzvah of the day is teki�at haShofar. You want to make sure that the sound of the shofar is powerful that it rings in your heart for at least the full Aseret Yemei Teshuvah, the full Ten days of Repentance.

Jews, like us, who are interested in making Jewish choices in this world, have one of two options when it comes to shofar blowing. We can either blow the shofar or we can hear the shofar. We can either sound the alarm or we can heed the alarm. We can either expose an injustice (sound the alarm) or we can pursue the injustice (heed the alarm). There are other choices available to us. We can remain silent about an injustice witnessed or we can ignore an injustice that has come to their attention. These are choices too and they are choices available to us at all times. They are real choices; they are just not Jewish choices.

Eizehu gibor? Who is courageous? So Pirkei Avot (4:1), the Ethics of our Sages ask. Hakovesh et yitzro. We who prevail upon our yetzer, upon our inclination. Which inclination? The yetzer hara, the evil inclination. The inclination to be blind or deaf in the face of moral wrongs.

Let's talk about Jewish piety in the 21st century. If you�re a Jew, and you see something going on around you that's wrong, that's illegal, that's immoral, that's hurtful, that's dishonest, and you know that you�re dealing with a superior whose fundamental rule for all his subordinates is to keep your mouth shut, then I want you to know that the most pious and holy thing, the most sacred action you can do at that point is to scream the truth, disrupt the order, buck the system, and upset the apple cart. No one can control you. No one can stop you. No one can suppress you. No one can tell you to keep your mouth closed. We diminish our humanity when we allow ourselves to be sucked into someone else's delusion of power or control. But how do we make that decision? Where do we find the courage to wrest ourselves from the grip of these pressures?

If you�re asking yourself that question, and it's ok if you do, you�re on the right track. A hospice caretaker recently wrote about what she had learned from the patients she had worked with over the years. She was particularly interested in their regrets, perhaps so that she could address some of those misgivings and disappointments at a time when a person is inclined to leave this world guilt-free or with a clear conscience. What she discovered was that even at the end of life, when the threshold between this world and the other is merely a handful of days away, people continue to grow. They grow because they finally have the time to think, to assess, to review what has been going on in their lives. What did they regret? They regretted having worked so hard, having lost contact with old friends, and having denied themselves pleasures that would have otherwise brought them joy.

And on top of those regrets were two of great interest. They regretted having not expressed themselves as honestly as they could have and the saddest regret of all�having lived not their own life, but the life that others expected them to live. They perceived themselves as having lived up to the expectations of others, while having either denied themselves their own or having never taken the time to consider what their expectations of themselves were.

All this leads back to Goldberg's Pencil Factory. Goldberg was right. Everything we do will always leave a mark. There are some people in this world who would keep us from making that mark, from getting out our lead. If we don�t leave a mark, that too is a mark, but one we may not be too proud of in the end.

Will there be times when we make a mistake? Of course. Lots of mistakes can be erased. Sometimes it's in the erasing that we learn the most about who we are and the world around us. Don�t be afraid to make the mistake and don�t be too proud to use your eraser. It's not always easy speaking up. We know that whistle blowers or people who speak truth to power are not compensated for their efforts with gold or compliments. None of us want to endure the lashings received for challenging the people who do wrong. But there is, nonetheless, a great benefit in staying true to our own convictions and that is our opponents will not weaken us they will sharpen us. The sharpening will be painful, but in the end those experiences make us stronger. To paraphrase mark Twain, Doing the right thing has its benefits. You will gratify some people and amaze everyone else. And you will always know that what matters most isn�t them, the outside, but it's you and what is on the inside. You can shut up the voice inside of you that demands of you to do what is right, but why shut up that voice? That voice, that sound is meant to be heard. It is meant to be given expression.

And then there is this hand that guides us. Here things become tricky because we have to distinguish between the hand that guides us and the then hands that grab us by the collar and tell us to Shut up. The hands that cover our eyes or our mouths and demand that we�ve seen nothing or heard nothing. Those are the hand we dare not let guide us. But rather that gentle nudging hand that moves us to acts of courage and declaration of truth. That's the hand that guides us. It is the hand of God. We allow it to push us even though we tend to go our own way but even then, even when we are off track, the hand is there giving us little nudges and pushing us in the right direction. We may not recognize the wisdom of that direction but it is always the direction of who we were meant to be in this world: not a slave, not an animal, not mindless or gutless, not silent or fearful, not cowardly or timid, but a human that is blessed in partnership with God.

So in the end, here's the message. We can sound the shofar or heed the shofar. Those are the Jewish choices. And we all need to be better pencils.

Ketivah Vehatimah Tovah�May we all be written and sealed into the Book of living and Life for a great New Year.